I have just finished reading Signal. Image. Architecture. by John May, a principal of MILLIØNS, an architecture practice based in L.A.

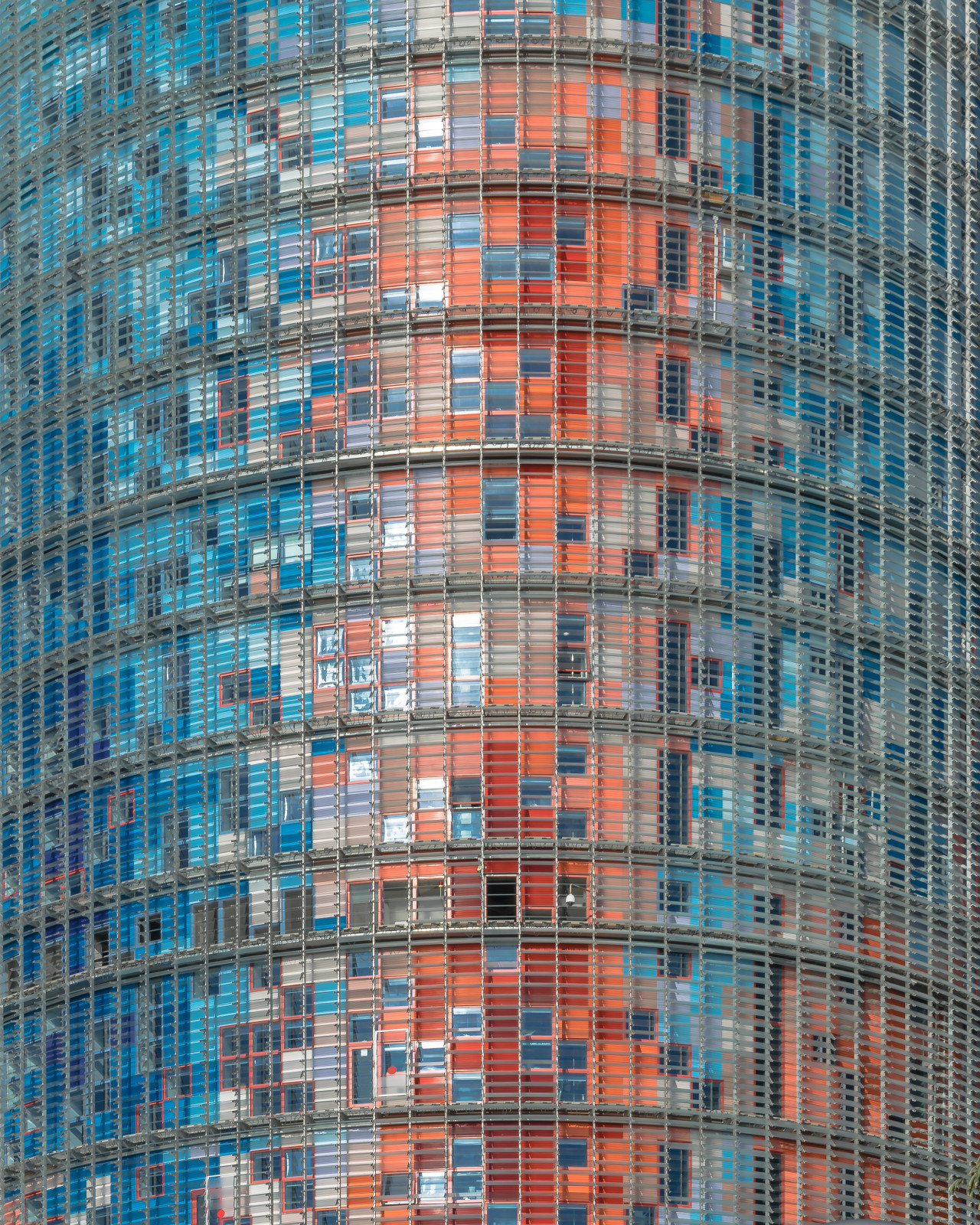

May makes a compelling argument that drawing and orthography in general are over and out: totally subsumed by a technics of imaging, at least since 1982 when AutoCAD first published its software (and undoubtedly before that). We now incubate and multiply images as electromagnetic patterns on screens, and occasionally ‘print’ them by depositing ink or residue on paper, but the resultant product is no more a drawing than a digital photograph of a drawing is.

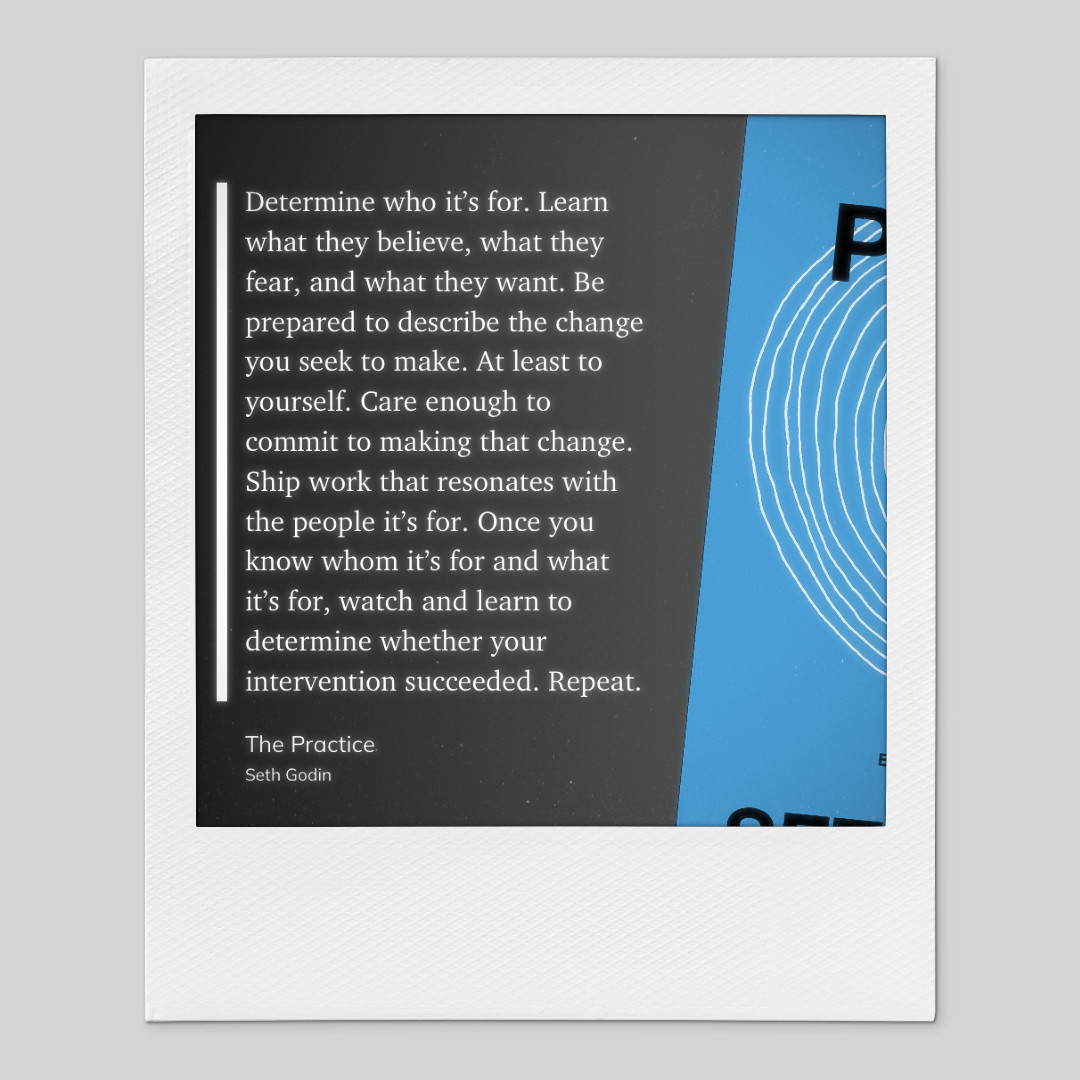

So what does it mean to accept that drawing is ‘over’? Certainly, it touches a sense of disquiet I have been harbouring professionally, noting that younger graduates, students, and architects have no relationship with drawing at all. Absolutely none. They are digital-first and image-focused, and don’t know how to use their hands to produce a mark.

Much more than a simple skill deficit, this is indicative of and significant as an entirely new, emergent, methodology of technical production. A culture of orthographic production, with its attendant relationship to history and temporality itself, has been replaced with a culture and technics of imaging.

In our architecture practice we use that tyrannical program, REVIT, to assemble three-dimensional models of potential buildings. The fact that architecture is still hand-made and hand-assembled, stick by stick, from two-dimensional artefacts, is sometimes lost on our younger staff. We need to have those two-dimensional images composed in a particular way that mimics orthography, at least for now - until the digital model becomes the instrumental apparatus of actual construction (and we are not there yet).

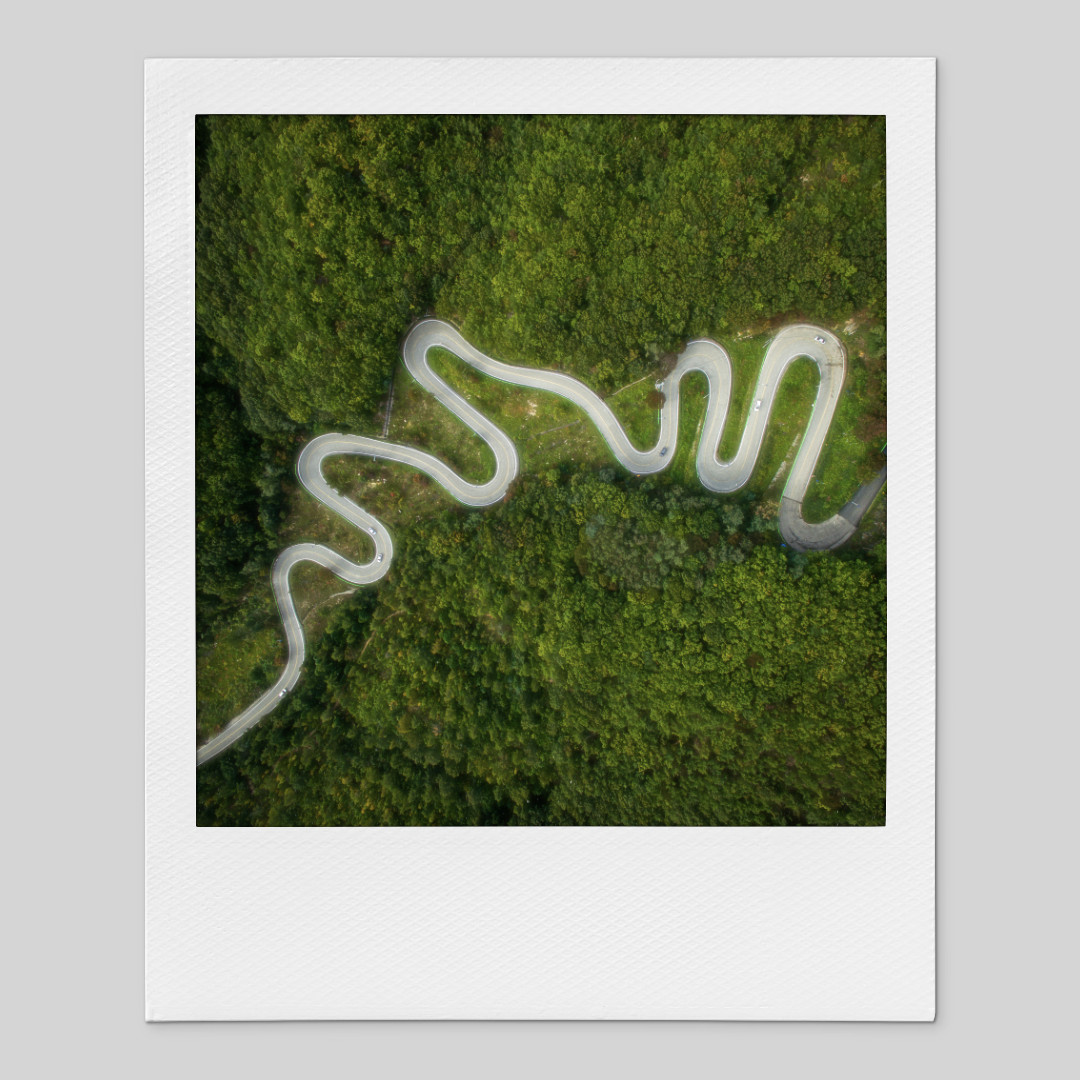

As such, we (the elders of the practice) find ourselves attempting to teach digital natives about the difference between a ‘section cut’ command or function in REVIT, applied instantaneously to a virtual model, and an actual section as a legible type of document. Our sections may only be an imitation of a drawing, but as a pseudo-orthogonal object that a builder can interpret owing to the conventions of the two-dimensional outcome, it has instrumentality.

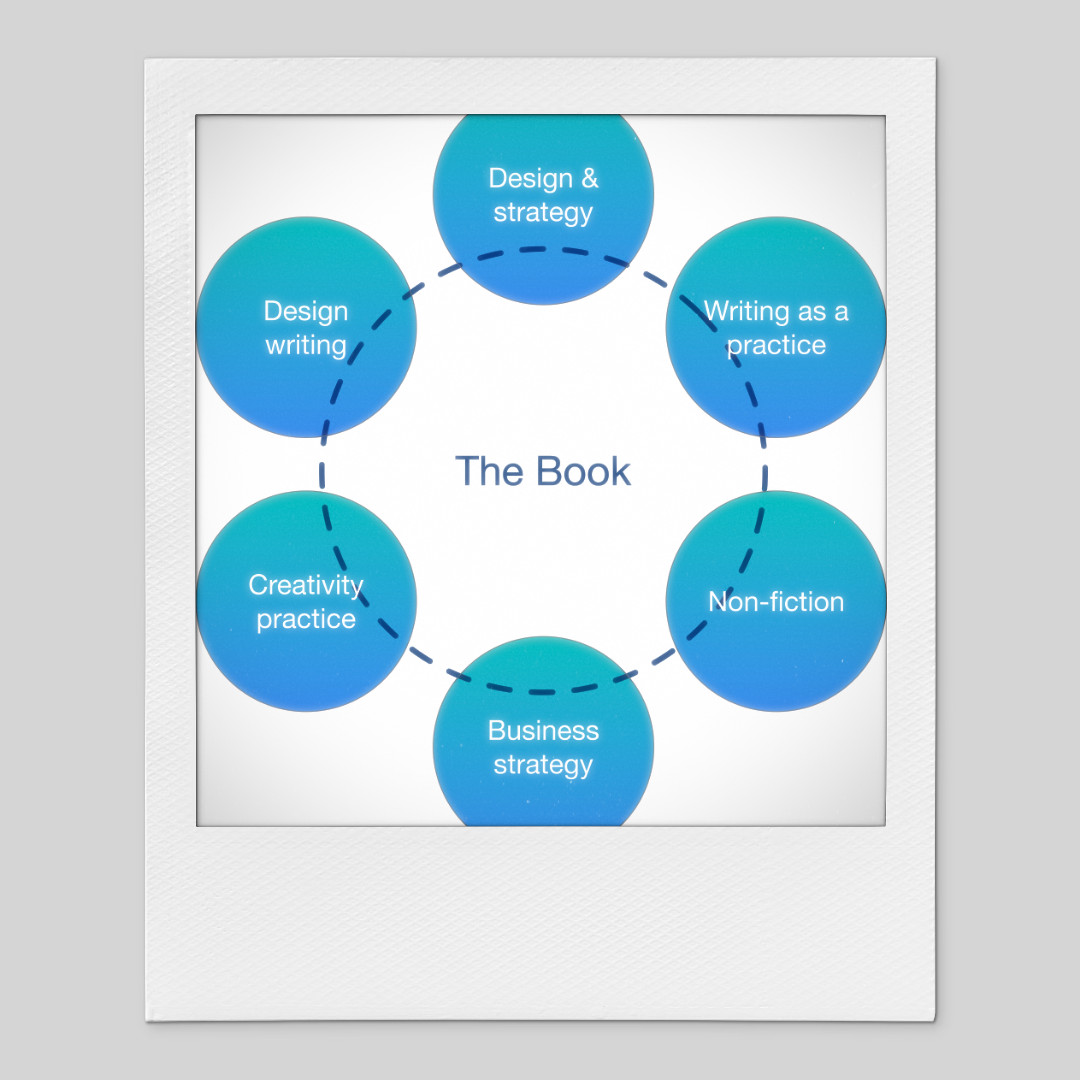

Which leads me to the book. What does it mean to say that design writing can be like ‘drawing with words’, in a field (and world) where drawing is now defunct? I’m a bit stumped. ‘Drawing’ was always only an analogy in that construction: is it still valid to illustrate a point with an analogy tied to a defunct, pseudo-practice like drawing?

No idea. I will ponder.

0 Comments