Telling stories about architecture and interior design is not like telling stories about brands, objects, or experiences. Let's focus on architects for a moment: they are my tribe, I know a lot about them, and their behaviours are pretty distinctive.

Architects are typically very bad at explaining what they do and have done without resorting to a codified industry language that is part professionally exclusive, part academically elusive, and 100% alienating to interested and intelligent lay people. Architects almost seem to want to protect their professional and vocational obscurity, in a way akin to that of the legal and medical professions, with their traditional reliance on latin for the same purposes. What this means is that the profession typically finds its most appreciative audience for its obscure utterances not in clients and potential users, but in other architects - those who are initiated into the creed. I can't overstate how boring this is to me, and how counterproductive it is to the vitality of the profession. It is the reason I don't attend conferences that exclude clients and common-or-garden users.

There is a website rather obscurely and awkwardly called the UpGoer 5 (https://splasho.com/upgoer5/) which challenges you to explain anything using only the 1000 most used words in the English language. "Architecture" is not one of those 1000 words, and nor is "design". I challenged myself to define architecture using the tool, and came up with the following:

"Places and spaces that are more interesting than other places because people have thought hard about how they are made and have made them carefully. These places and spaces are all around us but some are more important than others because of how they are made. We study, talk and write about those important places and spaces. We change old ones sometimes, and we make new ones other times. Some people do this for a living."

The above definition passes the 1000-most-used-words-only test, and constitutes a definition of architecture that gives insight into the process and product (verb and noun) of the profession, as it is practiced by trained professionals. And yet, it is easy to understand, without diminishing the complexity or even magic that happens when you get design right as a trained professional.

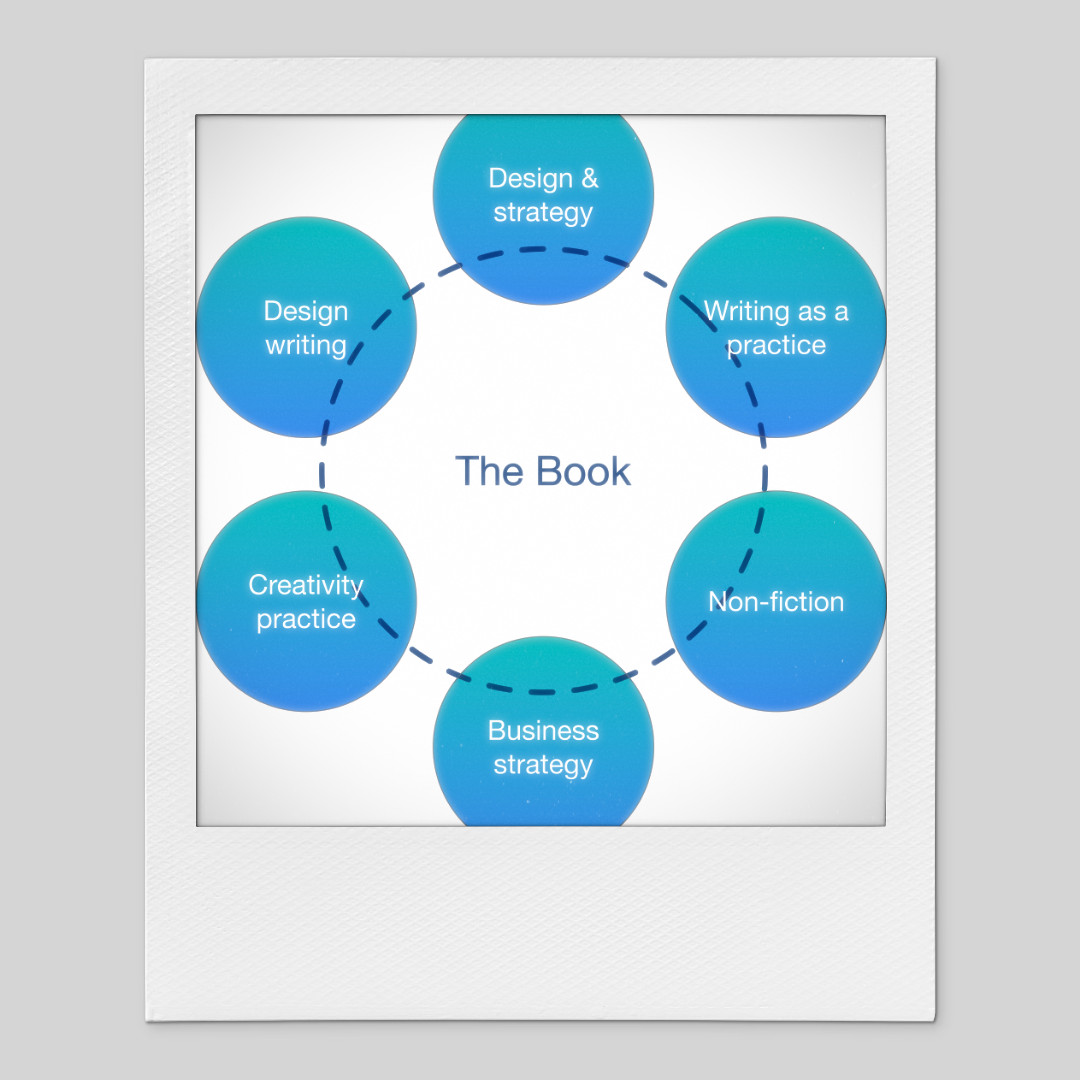

The book Writing Design is a departure for me, in that it is intended to speak to the design professional first, and the interested lay person second. Almost all of my published writing has inverted that relationship. I write in journals to speak primarily to intelligent non-professionals, and I delight in conveying the undoubted complexities and subtleties of the design process and product in language that is fundamentally easy to understand. I aim to be the opposite of professionally opaque.

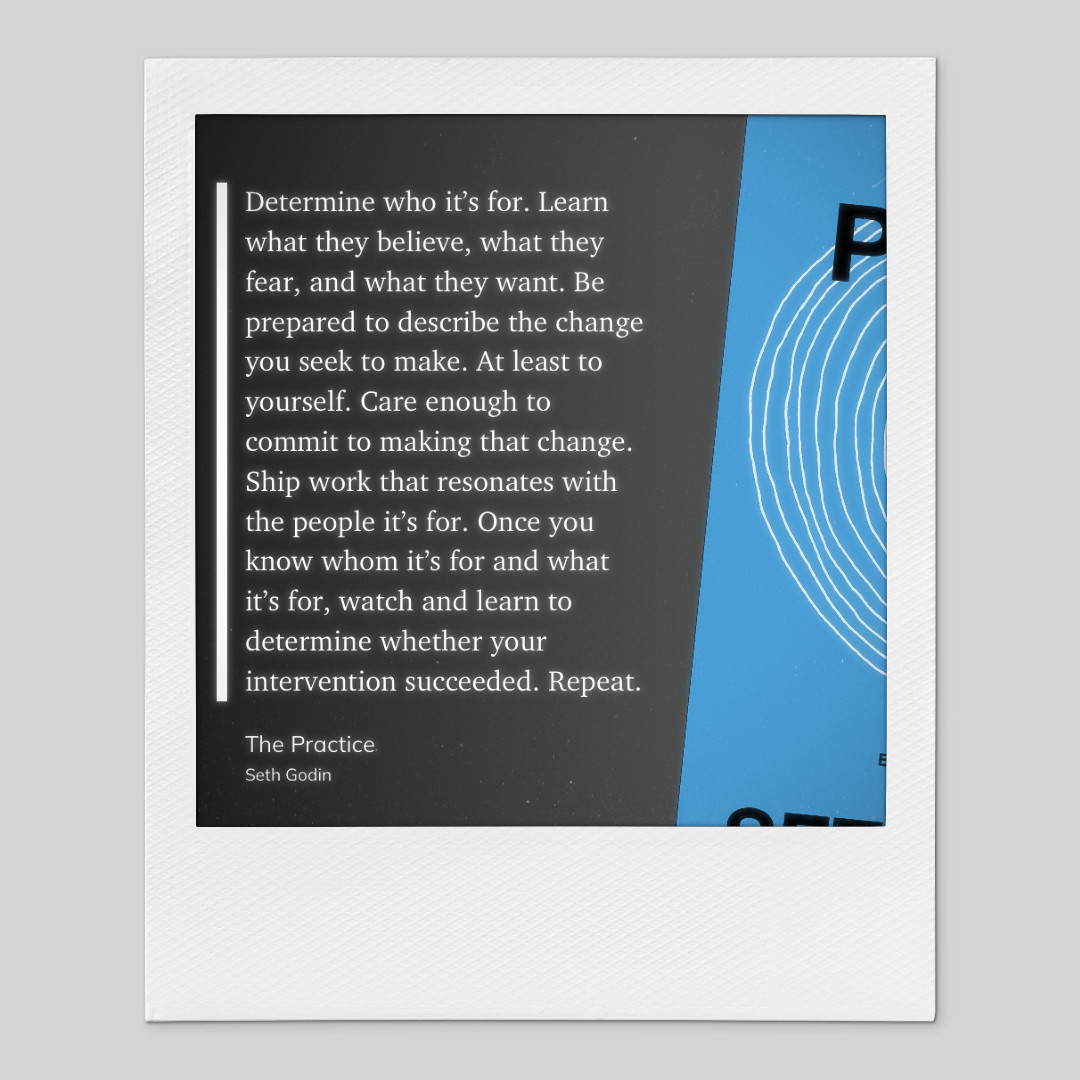

That, for me, is the sweet spot: architecture, interior design and other forms of design are all magical in their own way. Sharing this magic in a way that can be communicated clearly and understood beyond the realm of the initiated professional cohort seems like a no-brainer to me. It is sound conceptually, not professionally lazy, and frankly good for the bottom line: designers need customers and buyers, and wilful professional obscurity is a poor substitute for the power of clear and robust communication.

Photograph © 2019 Gussy Lowenhielm

0 Comments